Global Education Paradox: How One Nation’s Academic Progress Can Trigger Another’s Industrial Decline

The connection between educational development and global industrial shifts

When a nation importantly improves its education system, the effects ripple far beyond its borders. These educational advancements can trigger complex economic transformations that sometimes lead to deindustrialization in other countries. This phenomenon represents an oftentimes overlook dimension of globalization and international development.

The relationship between one country’s educational progress and another’s industrial decline involve multiple economic, social, and political mechanisms. Understand these connections help explain shift global manufacturing patterns and provide insights for policymakers navigate international economic relationships.

How educational improvement create skilled labor forces

Educational advancement typically begins with enhance access to quality education, improve curriculum, better teacher training, and increase educational funding. These improvements produce a workforce with stronger technical skills, critical thinking abilities, and innovation capacity.

Countries that successfully upgrade their education systems oft experience:

- Higher literacy and numeracy rates

- Greater technical and scientific expertise

- Enhanced problem solve capabilities

- Improved adaptability to new technologies

- Stronger innovation ecosystem

As these educational gains translate into workforce improvements, nations become more competitive in higher value industries. South Korea exemplify this transformation, having evolve from a principally agricultural economy to a global technology leader through sustained educational investment.

The transition from manufacturing to knowledge base economies

Advantageously educate populations course gravitate toward higher skilled, knowledge intensive sectors. This shift creates economic pressure to move beyond basic manufacturing toward advanced industries like:

- Information technology and software development

- Financial services

- Research and development

- Advanced manufacturing

- Professional services

As workers gain more education, they typically demand higher wages that reflect their enhance productivity and skills. This wage pressure makeslabor-intensivee manufacturing less economically viable within that country.

Singapore demonstrates this pattern distinctly. Its exceptional education system help transform the nation from a manufacturing hub into a global center for finance, technology, and biomedical sciences. This transition create prosperity forSingaporee but contribute to manufacture shifts throughoutSoutheast Asiaa.

Comparative advantage and industrial migration

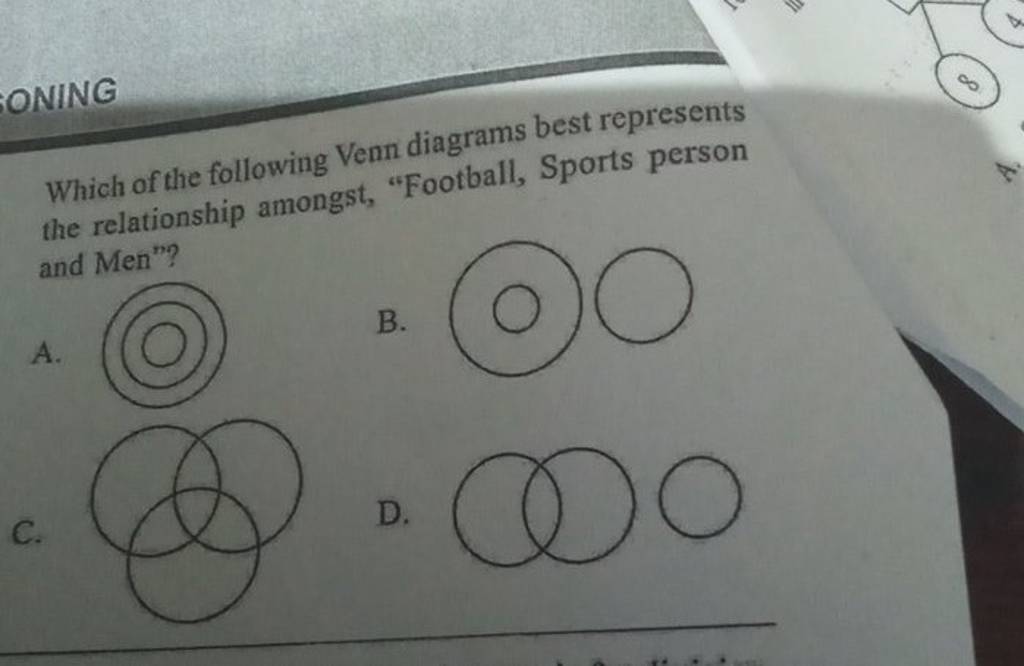

The concept of comparative advantage explain much of how educational improvements drive industrial relocation. As a country’s workforce become more educate, its comparative advantage shifts toward knowledge intensive industries sooner than labor-intensive manufacturing.

This economic principle creates a natural incentive for manufacturing to migrate to regions where:

- Labor costs remain lower

- The workforce match manufacture skill requirements

- Infrastructure support industrial production

- Regulatory environments favor manufacture

When manufacture relocates from educationally advanced nations to countries with less develop education systems, the recipient countries gain industrial capacity while the originate country experience deindustrialization.

The massive shift of manufacturing from the United States and Western Europe to China begin in the 1980s part reflect this pattern. As western workforces become progressively college educate, manufacturing find a more suitable home in China, which offer millions of workers with appropriate skills at lower wages.

The role of multinational corporations in industrial relocation

Multinational corporations act as primary agents in transfer industrial capacity between nations. These companies invariably evaluate global locations to optimize their operations base on workforce capabilities, costs, and market access.

When a country improves its education system, multinationals may respond in several ways:

- Relocate basic manufacturing to less educate, lower wage countries

- Establish higher value operations in the educationally improve nation

- Create global value chains that distribute different production stages across multiple countries base on their educational strengths

This corporate decision-making accelerate deindustrialization in some regions while drive industrialization in others. The electronics industry demonstrates this pattern intelligibly, with design work concentrate in extremely educate regions while assembly operations locate in areas with appropriate workforce skills and lower wages.

Technology transfer and industrial capability building

Educational improvements enable countries to absorb and implement advanced technologies more efficaciously. This capability allow nations to move up the value chain, take on manufacturing activities that antecedent occur elsewhere.

The process typically follows this progression:

- A country improve its education system, specially in technical fields

- To emerge skilled workforce become capable of operate advanced manufacturing systems

- Foreign companies transfer production technology to take advantage of this workforce

- Local engineers and technicians master these technologies

- Domestic companies emerge that can compete internationally

This pattern has play out repeatedly across East Asia. Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and forthwith china have followed similar trajectories, each absorbing manufacturing capabilities from more develop economies as their educational systems improve.

Wage competition and industrial hollowing

As education levels rise, workers course command higher wages. This wage growth makeslabor-intensivee manufacturing less competitive compare to regions with lower labor costs.

The result wage differential creates economic pressure to relocate manufacturing operations. Industries peculiarly sensitive to labor costs — like textiles, footwear, and basic electronics assembly — are oftentimes the first to migrate.

This process can lead to industrial hollowing, where manufacturing employment decline chop chop in the more educate nation. The United States and United Kingdom experience this phenomenon dramatically in the late 20th century, lose millions of manufacture jobs as production shift to countries with lower cost labor forces.

Consumer preferences and domestic market evolution

Educational advancement typically correlates with rise incomes and evolve consumer preferences. As populations become more educated and affluent, they oftentimes demand:

- Higher quality goods and services

- More sophisticated products

- Greater product variety

- Enhanced customer experiences

- Products with stronger brand identities

These change preferences shift domestic markets aside from basic manufacture goods toward premium products and services. This market evolution far encourages the transition forth from basic manufacturing toward higher value economic activities.

Japan’s evolution illustrate this pattern distinctly. As Japanese education and incomes rise, consumer preferences shift toward higher quality goods, strengthen Japan’s premium manufacture sectors while basic manufacturing move to other Asian countries.

Policy responses to educational disparities and industrial migration

Nations face deindustrialization due to educational disparities much implement policies to address these challenges. Common approaches include:

- Industrial policies to support advanced manufacturing

- Workforce retrain programs

- Educational reforms focus on technical skills

- Research and development incentives

- Trade policies to manage industrial transitions

Germany has maintained a stronger manufacturing base than many likewise develop economies through its dual education system, which emphasize technical training alongside academic education. This approach has help preserve advanced manufacturing still as basic production harelocatedte elsewhere.

Source: educationnext.org

Case studies: education drive industrial transitions

China and Mexico

China’s dramatic educational improvements since the 1990s have enabled it to move up the manufacture value chain. AsChinesee workers become more educated,labor-intensivee manufacturing hasbegunn shift to countries likeVietnamm,Bangladeshh, andEthiopiaa. Meantime,Mexicoo has experience partial deindustrialization in sectors where itcompetese direct with china’s progressively skilled workforce.

Japan and Southeast Asia

Japan’s exceptional educational system help transform it into an advanced economy. As Japanese workers become extremely educate, labor-intensive manufacturing relocate to southeast Asian nations with less develop education systems. Countries like Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia industrialize partially by receive manufacturing activities that were nobelium yearn economically viable in Japan.

United States and china

The United States have experience significant manufacturing job losses as production shift toChinaa and other countries. While multiple factors drive this transition, the mismatch betweenAmericaa’s extremely educate workforce and the labor requirements of basic manufacturing contribute importantly to this industrial migration.

Source: ncebengal.com

The double-edged sword of educational development

Educational improvement present both opportunities and challenges for nations. While it enables economic advancement and higher living standards, itto necessitatee difficult economic transitions.

Countries experience education drive deindustrialization oft face:

- Regional economic disparities as manufacturing centers decline

- Workforce displacement require retraining and adjustment

- Political tensions around trade and globalization

- Challenges maintain balanced economic development

Meantime, countries receive relocate industries gain employment opportunities but may become vulnerable to future relocations as their own education systems improve.

Future trends in education drive industrial shifts

Several will emerge trends will shape the relationship between educational development and industrial location:

Automation and advanced manufacturing

Increase automation may reduce the labor cost advantage of less educate workforces, potentially slow manufacturing migration. Yet, operate advanced manufacturing systems require advantageously educate workers, create new forms of educational advantage.

Digital services and remote work

The growth of digital services and remote work create new channels for educational advantages to affect global economic patterns. Intimately educate workforces can provide services globally without physical relocation of industries.

Sustainability concerns

Grow emphasis on environmental sustainability may encourage shorter supply chains and local production, potentially counteract some pressures for industrial relocation base strictly on educational and wage differentials.

Balance educational progress and industrial stability

Nations can pursue strategies that promote educational advancement while manage industrial transitions:

- Develop education systems that balance academic and technical training

- Create pathways for workers to transition between industries

- Invest in research and innovation to create new industrial opportunities

- Form international partnerships that support reciprocally beneficial development

- Design trade policies that allow for gradual industrial evolution

Countries that successfully navigate these challenges can achieve educational progress without suffer the virtually disruptive aspects of deindustrialization.

Conclusion: the global educational ecosystem

The relationship between educational improvement and industrial relocation highlight the interconnect nature of the global economy. One nation’s educational advancement needs shape economic opportunities elsewhere, create a complex web of dependencies and transitions.

Understand these connections help policymakers design education and economic strategies that recognize global realities. Sooner than view deindustrialization entirely as a threat, nations can approach it as part of a broader transition toward knowledge base activities that leverage their educational investments.

The virtually successful countries will be those that can will adapt their education systems, industrial policies, and workforce development strategies to the invariably will evolve global landscape. By embrace the educational progress of all nations while manage the result economic transitions, the world can achieve more balanced and sustainable development.

MORE FROM yourscholarshiptoday.com